Augmented Reality: Fleeting Gadget or Platform of the Future?

Ten years ago, the unveiling of the first iPhone initiated a revolution in our relationship with technology. Since then, smartphones have shaped human behaviour to a greater extent than when the general public first discovered the Internet to the tune of 48k modems.

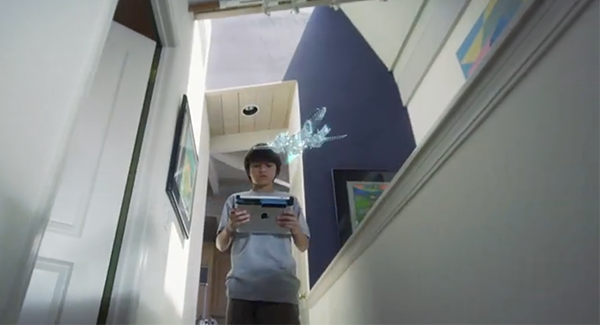

And it would be a safe bet to say that the impending release of the iPhone 8, expected in September, will initiate a similar revolution by introducing augmented reality into our everyday lives whereas, only a few years ago, it was widely considered a gimmick for Hollywood science-fiction flicks in lack of inspiration (e.g. Creative Control). Indeed, besides Apple, Google (with Tango) and Facebook (with AR Studio) have both set their sights on AR, offering a glimpse of a world where pixels and reality combine, opening a path towards Digital Reality IRL. Feast your eyes!

It’s been coming for a while: Google Glass, Microsoft HoloLens, Snapchat, Pokemon GO… Augmented reality is shaping up to be more accessible to the general public than VR, which remains more popular amongst developers and gamers due to its material and logistic requirements. Though AR is still currently limited to niche publics and gadgets, the big five clearly see it as a new, unavoidable paradigm.

This can be seen by the gradual disappearance of screen edges (Samsung S8, iPhone 8 etc.), the ever more efficient sensors (such as those which measure distance through time-of-flight) and the cameras capable of creating 3D models of space as easily as scanning a QR code. All this aims to augment reality without giving the user the feeling of watching a Z movie with comical – rather than credible – special effects.

The smartphone is the perfect tool to initiate this change. Connected glasses and lenses may await the user in a not so distant future, but the screens of our phones and their cameras have already upgraded our retinas in our everyday relation to reality. We can watch Waze project a route onto our windscreens (HUDWAY), or hunt monsters in the public space through our smartphone screens. The upcoming iPhone 8 will include laser sensors to measure distance through time-of-flight.

Apple’s gamble – whose ARKit framework, unveiled in June, will allow the greater public to benefit from AR apps come September and the arrival of iOS 11 – continues on the user centric path which made the success of the iPhone (primarily an iPod with telephony and Internet access) and Facebook (originally a simple network allowing students to connect online). Simple solutions to relatively basic needs are a shorter path to global revolution than spectacular and futuristic concepts. Though the latter may be eye-catching, they rarely facilitate everyday life, which is ultimately one of technology’s main goals.

However, advanced technologies such as, for example, the Structure Sensor camera for iOS, or Facebook’s implementation of the SLAM algorithm (Simultaneous localisation and mapping) which allow to work in 3D – and thus AR – with very little hardware (or even none at all), should not be neglected in the grand scheme of general public-oriented augmented reality. Nonetheless, these technologies will have to be put to use in serving the often mundane needs of users, in order to progressively bring them towards a revolution which, though slower than that brought about by the smartphone, will happen on a similar scale.

Rather than offering experiences which are impressive but short-lived, or which require heavy investment (be it in time, money, or even space), such as immersive experiences in virtual reality, the major challenge for tech and digital agencies is to avoid the easy pitfall: losing users by trying to amaze them rather than addressing their real needs.

Though it seems clear that, by 2020, augmented reality will have profoundly changed our everyday lives, the success of industry actors will ultimately depend on their capacity to progressively bridge the physical and digital realities without getting too far ahead of themselves. It is of course tempting to fathom a world in which we have constant access to an extra layer of virtual information, transparently completing the reality in which we live. But we must learn to walk before we can run. Otherwise, we trip and fall, which can weaken our desire to become athletes. Most importantly, it means not confusing Research and Development with successful user experience. The tools whose success lives on are those which make themselves unavoidable, rather than those which shine bright but burn out fast.